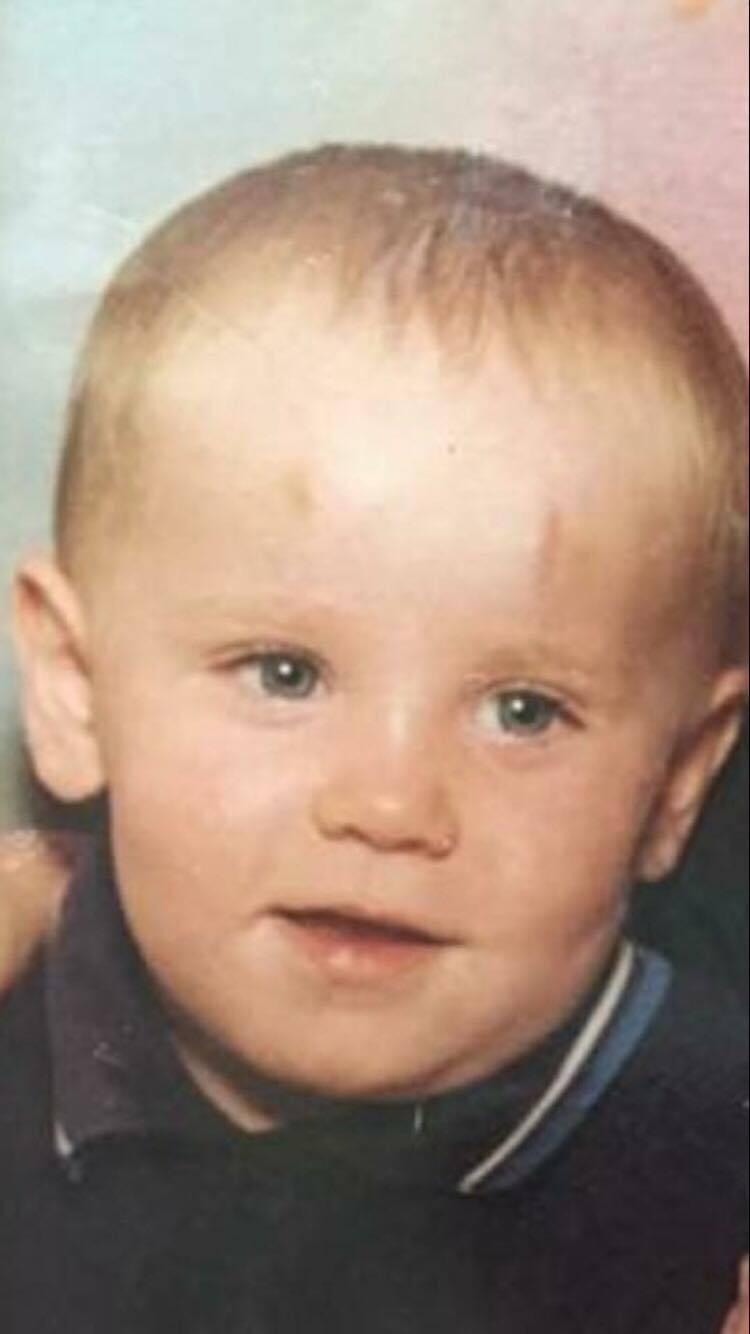

Aaron KEENAN is everywhere in his family home.

His dad Paul and brother Christopher have his name tattooed on their arms. His image is in all sizes around the living room.

Just to the left of the front steps of the Whitecrook home is a memorial stone with a “67” for the beloved Lisbon Lions – Celtic’s European Cup-winning side – surrounded by garden lights and flowers.

In front of it is artificial grass the width of the front garden for his brothers to enjoy kick-about and to the left “Aaron’s Gaff”, a hut that will eventually be filled with memories of the 19-year-old.

One year on from his death on the rail line near Kilpatrick station, the family remain as grateful as ever for the support of the entire community. Their need for that in the face of overwhelming grief has not diminished.

They move forward from day to day in different ways. Paul admits he shuts it out so “people can see someone strong”, while mum Gillian finds it harder, all while trying to hide it from her children, whom she knows are finding it difficult.

“I never have a good day – I just have better days,” says Gillian, 42. “Although it’s happened it’s still that realisation I’m not going to see him again. You just can’t believe it even after a year. All of us are really struggling. I just feel I’m here for the rest of them every day. We function for them.

“I always need to make time for Aaron. I go to his grave a lot. That’s all I can do for him.”

The year has been one of firsts – the first Christmas without Aaron, his 20th birthday last month, his dad’s 50th. Mother’s Day. Father’s Day. His siblings’ birthdays.

“You get constant reminders,” says Paul. “Some times are harder than others. Other times, you can cope with it.

“It’s been a nightmare year.”

*****

Around 5.30am on June 25, 2017, Aaron was heading home from a party along the rail lines. For whatever reason, he fell asleep near the rail line.

His family believe he was woken by the train horn from the first train heading to Balloch to begin the day and he turned and was struck. The only injury beyond some scratches was to his forehead, but it proved catastrophic.

One of the first on the scene was a paramedic who was not called out but lived nearby and rushed to help. A friend of the family, he saw the boy’s ID – Aaron was carrying that of his older brother Christopher – prompting the paramedic to head straight for Whitecrook to alert Gillian and Paul to get to hospital.

The BTP officer on the scene knew the family. The ambulance driver who took him to hospital also knew them.

At the funeral, Gillian recognised every face – Aaron was so well-known and liked the chapel was overwhelmed.

Paul acknowledges a “couple people think” Aaron killed himself, but he knows it was a tragic accident. He knows the difference, having had to identify the clothing of his own brother when he put himself in front of a train.

“If it had been another 4-5 inches away, Aaron wouldn’t have got touched at all,” says Paul.

“He would have come home with a fright and told us how stupid he had been,” adds Gillian.

She has visited mediums and says Aaron has told her he was sorry.

“He would go to sleep anywhere when he had too much to drink,” she says.

Paul says that while it’s possible Aaron fell and hit his head, they believe he fell asleep.

“Our firm belief is he was going to get to Kilpatrick station and have a seat until the first train came along,” he adds.

“Six or seven times out of 10 he would phone you and say he was stuck. He never did it that morning. There’s lots of ‘what ifs’ you could go through.”

The family has pushed for more bereavement training in schools as they watch their own children work through their pain, each in different ways. Eoghan, seven, tries to refrain from talking about it. Jack, 12, is harder to gauge. Daughter Niamh, 17, recently did the Kiltwalk and raised £900 to go towards the ICU.

But they have been overwhelmed by the support of their family, friends and all of Clydebank.

Paul repeats his gratitude for the community that kept their living room filled with well-wishers, the “astonishing” turnout at his funeral, the donations from others, and particularly for those at Aaron’s side on the morning of the accident.

“The help and support around this area and the town in general has been second to none,” he says. “We want to thank the public, the friends, family and beyond from the bottom of our hearts.”

“It’s been non-stop support,” adds Gillian.

*****

Aaron would come in every night and make a crack about his mother’s cooking, but happily clear the fridge of almost anything.

Dubbed “The Waterbhoy” by players on his father’s team, Duntocher Hibs, he loved his family, his friends, and shared his sense of humour with anyone.

While their other children might protest about picking up something from the shops, Aaron would be straight out the door to help, says Gillian. But he would probably meet five people he knew on the way there and back and he would never pass them without having a chat.

“He made me greet, but he made me smile,” says his mum.

“He had a heart of gold,” adds his dad.

In the hours before the accident, Aaron was hanging out with old friends from nursery and Our Holy Redeemer Primary. Later, he was with his friends from his time at St Peter the Apostle High. “It was as if it was meant to be,” says Paul. “Maybe it’s crazy. It was all people who knew him on the scene. It was just surreal.”

Gillian says it’s all comforting that people he knew kept talking to him in the hours following the accident.

“I believe he was breathing hard so we could all say goodbye to him,” she adds.

As Aaron lay in hospital, his friends and loved ones flooded to

his side, and Gillian insisted they would all have the chance to say farewell. The nurses let them in two by two, and later in fours. She shared him with the town and, a year on, she knows she wouldn’t change how it went.

Paul asked Eoghan if he wanted to see Aaron. He took him into the room and picked him up.

“He leaned over and gave him a kiss and he passed away,” recounts Paul. “It was as if Aaron was waiting for it.”

“I just thought we had forever,” adds Gillian.

“It’s a tragedy,” says Paul, “but on the day, it was probably perfection.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here