TODAY, the NHS is a prized institution dominating political debates, employing tens of thousands and saving countless lives every hour of the day.

But 70 years ago in Clydebank, its birth merited barely a mention.

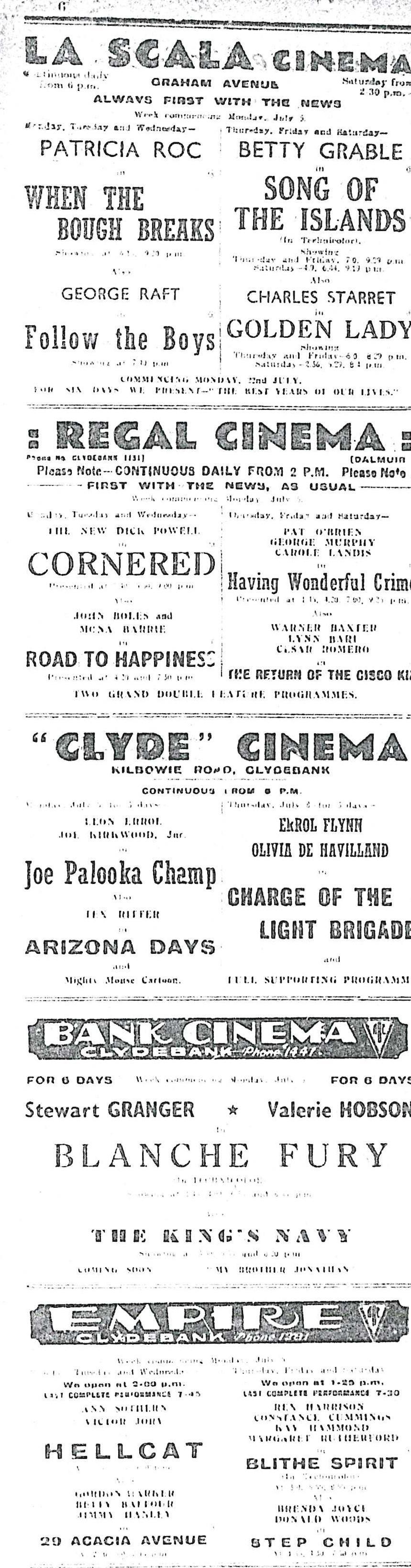

In the Clydebank Press editions of July 1948 there were just four broadsheet pages packed with wedding announcements, the latest at the town’s five cinemas, the sports results, and ads, such as for surplus RAF slippers.

Media was truly social, recounting the arrivals and departures of residents and visitors, and many articles on the Clydebank Burgh Band.

And on July 2, 1948, there was a small reference that read: “National Health Service, Dunbartonshire Executive Council, Dunbarton Burgh Insurance Committee.

“Intimation is hereby given that the office of the above council committee will be situated at the lesser burgh hall, Church Street, Dumbarton, as from 1st July, 1948.”

On July 9, days after the NHS formally came into being on July 5, there was no mention at all.

A week later, next to the snooker ad - “those with ‘nuts’ ‘screwed’ on right make a ‘bolt’ - and for those “triple-sewn fawn gabardine” slippers and Saxa salt, ran the report of a “bombshell” fight over the Townend Hospital.

It was originally built as a poorhouse on Townend Road, Dumbarton, and later became the Townend Poor Law Institution and had 186 beds in 1946 with a hospital of 78 beds.

After 1948, it was renamed Townend Hospital and later on, the Central Hospital to offer geriatric care.

But at a meeting of the department of health, the town clerk of Clydebank announced his council had changed their mind on the hospital and it should be transferred to state ownership instead of the local authority.

Dumbarton Town Council wanted the hospital kept locally and Clydebank’s position was branded “unfortunate” and “hasty”.

Some councillors appeared to have not been at a crunch Clydebank meeting over their position, reported the Press.

Mr Chisholm, for Dumbarton, described Clydebank’s decision as a “bombshell” and “they were now as likely to lose the hospital as retain it”.

And then on July 23 there is a proper announcement about the NHS, written in the familiar press release language still coming out of health boards in 2018.

A S M MacGregor, chairman of the Western Regional Hospital Board, welcomed “all who are employed in hospitals, clinics and allied branches and who are entering the new health service that is now beginning”.

He continued: “All these hospitals bring with them into the new administration their own high traditions of service to the public, for they have long since earned and won the confidence and affections of the people.

“It will be the duty of the Regional Board and of Boards of Management set up under the Act to maintain these services and to develop them as may seem best, in co-operation with those who work in them or who serve in a voluntary capacity.

“There are difficult problems ahead but I am confident that we can rely on the good will, help and experience of all those who have been associated with the hospitals in the past and who now in whatever capacity come over them.”

The Press was, as is the Post today, a mix of news, such as a lengthy report on “how not to start a fire”. Note: “Don’t smoke in bed!”

There was news on July 9 from Duntocher and Hardgate that County Councillor M Bissett said he was “hoping for the day when there would be a proper segregation” of pupils, with “the boy with academic bent set aside from the boy with the industrial or technical bent”.

There was a notice on July 16 about the new Ice Cream (Scotland) Regulatiuon requiring registration of any person for storage, manufacture or sale of ice cream.

Isobel Reid, of Glasgow Road, Clydebank, was fined for not cleaning her close.

And the Dalmuir father who had washed his hands of his son who stole a shirt from a tenement backcourt. But on hearing from the magistrate, Thomas Fleming, the 18-year-old agreed to behave and his father allowed him to return home.

“Father and son shook hands before leaving the court,” reported the Press.

But the dominant health-related coverage in the paper on July 16 and 23, 1948, was to do with the Blitz seven years earlier.

Clydebank’s medical officer of health, Dr Thomas M Hunter issued a new report for 1940-45 that offered what the Press called, “the first official, and certainly purely local account” of those two nights in March 1941.

Hundreds died, but number initially were difficult to calculate. Over two days, 40,000 of the total 50,000 people in the burgh were evacuated after the attack.

The report also said: “In Clydebank efforts had been made previous to the attack to obtain a list of mothers in preparation for an emergency such as occurred, but unsuccessfully. At that time, no name was submitted. But when the raid occurred large numbers of expectant mothers came wanting immediate evacuation. This last minute appeal was satisfied by Dr Neil Reid of Stirlingshire by accepting these mothers to Airthrey Castle.

“[They] escaped entirely the second raid.”

As well as details of the bombs and the response efforts, largely on foot, there was descriptions of how water supplies were affected.

A poster had been made in case such a disaster happened and copies were put up about the necessity of boiling water.

All food in shops was inspected, finding some damaged by glass splinters or debris or coal gas contamination.

The report found an “absolute necessity” to have one controller for a pre-arranged plan for an emergency.

But it noted: “Despite the fact that both the attacks, heavy and sustained, did an enormous amount of damage in a previously unattacked community, the morale of the population remained good and the services gave their best.”

So there was a report on Clydebank’s health service after all.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here