ITS doors closed for the last time almost 40 years ago, but the factory that once sewed together communities in Clydebank is still very much alive in the memories of those who worked there and their families.

The Singer sewing machine factory – so big it was effectively two towns within Clydebank, one for industrial production, the other for domestic machines – was home to ready-made jobs for life.

To mark National Sewing Machine Day earlier this month, some of those who experienced Singer first hand gathered at Clydebank Museum to share their stories with the Post.

William Sweeney was 15 when he first walked into the famous factory, which stood on ground now occupied by large shops in Clydebank town centre. He was sent there for an interview by his mother in 1956.

“I was a nervous wreck – the noise in there,” he said, describing the molten steel banging as it hit the moulds. “I remember saying, ‘I’ve got 40 years to spend in here?’ but I loved every minute.”

As well as the people working on both sides of the factory, and the outside activities connected with Singer such as sports galas, the Caledonian Ball and more, it was a community to be part of.

Tools could take three months to build, where now it’s done in 30 minutes, a modernisation that ultimately led to the demise of industrial life in Clydebank.

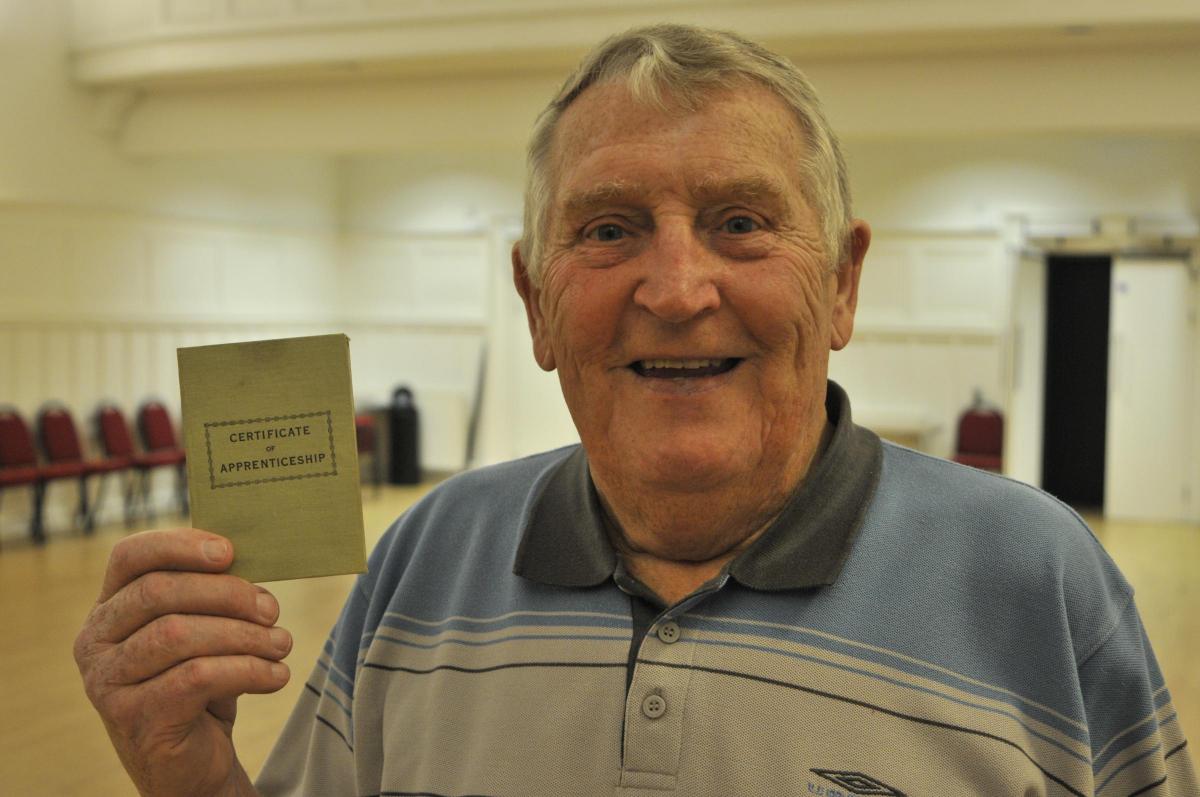

William began as a message boy, seeing all parts of the factory, then becoming an apprentice at 16. Remarkably he still holds his apprentice card five decades later.

He moved south for a time, but ultimately returned to Singer’s, as did his two sisters. Whole families worked there, and that contributed to the “tragedy”, as William describes it, when Singers closed in 1980.

“I was very very sad when the factory closed down,” recounts the 76-year-old. “It affected the whole town.”

Bailie Denis Agnew believes Singer is inseparable from Clydebank – with the factory actually pre-dating the town’s founding by two years.

He said rebuilding communities after the closure of heavy industry needs training and education to give young people hope and encouragement.

“I can see that when I see emerging talent coming through from schools and colleges and universities,” said Bailie Agnew. “We are going to have to realise it’s small units and small business and stores that’s the future.”

He said the days of ready-made life with a single employer were gone. And instead of those networks within one factory, such as Singer or John Brown & Company, now there were larger global networks with millions of people involved.

Chris Cassells is an archivist and collections officer with West Dunbartonshire Council for a catalogue that includes 800 sewing machines.

He said: “Stories like William’s give you insight into the era and society that simply doesn’t exist anymore.

“There’s something inspiring about how the people of Clydebank were at the forefront of industrial invention. There’s no reason they couldn’t be in the future.”

For William, there’s no forgetting the significance of saving the Singer history.

“When I started, I saw all these old sewing machines on the shelves,” he said. “Years and years later, the next time I saw them they were in Clydebank Town Hall museum and now I understand why they saved these machines.

“I don’t think the younger generation realises what Singer’s or John Brown’s meant to the town. I just give people the whole story now. I don’t know if it sinks in or not.

“I realise Singer’s and John Brown’s are gone forever – it’s a changed world. But I would like to think there’s someone in Clydebank who will invent something and bring something back to the town.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here